Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/priestly figure or spirits of dead ancestors or as a retainer sacrifice, wherein a monarch’s servants are killed in order for them to continue to serve their master in the next life. Closely related practices found in some tribal societies are cannibalism and headhunting.

Human sacrifice was practiced in many human societies beginning in prehistoric times. By the Iron Age (1st millennium BCE), with the associated developments in religion (the Axial Age), human sacrifice was becoming less common throughout Africa, Europe, and Asia, and came to be looked down upon as barbaric during classical antiquity. In the Americas, however, human sacrifice continued to be practiced, by some, to varying degrees until the European colonization of the Americas. Today, human sacrifice has become extremely rare.

Modern secular laws treat human sacrifices as tantamount to murder. Most major religions in the modern day condemn the practice. For example, the Hebrew Bible prohibits murder and human sacrifice to Moloch.

The Romans

The Romans, known for their sophisticated civilization, remarkable legal and administrative systems, and engineering prowess, have left an indelible mark on history. However, the practice of human sacrifice, which seems incongruous with their cultural and moral values, presents a paradox.

While it is true that the Romans did engage in human sacrifice at various points in their history, they also demonstrated a growing abhorrence for this practice.

This article aims to delve into the complex relationship between Romans and human sacrifice, exploring the factors that led to both its practice and eventual disapproval.

The Early Romans and Human Sacrifice Human sacrifice had a long history among pre-Roman Italian tribes. The early Romans, emerging from such a context, initially practiced it as well. This practice was rooted in religious beliefs that appeasing gods through the offering of human life would ensure prosperity and protection.

The Influence of Etruscans and Greeks The Romans’ contact with neighboring cultures, such as the Etruscans and Greeks, played a pivotal role in their evolving attitudes toward human sacrifice.

The Etruscans practiced human sacrifice, which influenced Roman beliefs. Additionally, Greek philosophy and religious ideas introduced a more rational and ethical framework that challenged the acceptance of human sacrifice.

Shifts in Religious Beliefs Over time, the Romans experienced a shift in their religious beliefs. The influence of Stoicism and other philosophical schools emphasized moral virtue, leading to a reassessment of the moral implications of human sacrifice.

Legal Regulations The Romans began implementing legal regulations that curbed human sacrifice. The Twelve Tables, a foundational legal code, included provisions against killing innocent citizens for religious purposes. This marked an early step in the direction of prohibiting human sacrifice.

The Punic Wars and Cultural Exchange The Punic Wars (264-146 BCE) between Rome and Carthage brought about increased contact between the two cultures. The Carthaginians, known for their gruesome child sacrifices, were viewed with horror by the Romans. This exposure further distanced the Romans from the practice of human sacrifice.

The Role of Religion in Politics Religion was deeply intertwined with Roman politics. As the Republic transitioned into an Empire, emperors began to present themselves as religious leaders. This shift in authority influenced the perception of human sacrifice, with emperors distancing themselves from such practices.

The Rise of Mystery Cults The spread of mystery cults in the Roman Empire provided alternative avenues for religious expression. These cults often eschewed human sacrifice, promoting personal salvation through initiation and ethical behavior.

Romanization and Integration of Conquered Peoples The Roman Empire expanded rapidly, incorporating diverse cultures and beliefs. The process of Romanization, which aimed to assimilate conquered peoples into Roman culture, often involved discouraging or prohibiting practices like human sacrifice.

Christianization of the Empire The rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire brought a new religious paradigm that emphatically rejected human sacrifice. As Christianity gained prominence, it contributed significantly to the decline of this practice.

Legal Prohibitions and State Intervention Throughout the Imperial period, the Roman state increasingly intervened to suppress human sacrifice. Legal measures were put in place to prevent such acts, reflecting a broader societal aversion.

Philosophical Discourse Roman philosophers, such as Cicero and Seneca, played a role in shaping public opinion against human sacrifice. They argued for a more enlightened and humane approach to religion and ethics.

Public Opinion and Ethical Concerns As Roman society evolved, public opinion shifted towards greater ethical concerns. The notion of sacrificing human lives for divine favor became increasingly incompatible with prevailing moral values.

Decline of Traditional Paganism The decline of traditional Roman paganism, which often involved rituals with human sacrifices in its earlier forms, contributed to the overall fading of this practice.

Emergence of New Religious Syncretism Syncretism, the merging of religious beliefs, allowed for the blending of various cultural and religious elements. This process often led to the abandonment of practices like human sacrifice in favor of more harmonious belief systems.

Legacy of Abhorrence By the time of the Roman Empire’s decline, human sacrifice had become a repugnant relic of the past. The Romans had moved away from this practice to such an extent that it was no longer a part of mainstream religious rituals.

Impact on Later Western Civilization The Romans’ evolving attitude toward human sacrifice set a precedent for later Western civilization, emphasizing ethics, rationality, and the sanctity of human life in religious practices.

The Carthaginians were worse

Historical accounts suggest that the Carthaginians, a civilization centered in the ancient city of Carthage in North Africa, practiced child sacrifice. This practice is often associated with the worship of the deity Baal Hammon (also known as Moloch), to whom these sacrifices were made. Carthaginian child sacrifice was particularly notable for its grim and controversial nature.

There is evidence, both archaeological and historical, that supports the existence of this practice among the Carthaginians. Ancient texts from various sources, including Greek and Roman writers, mention this practice, and there have been discoveries of Carthaginian cemeteries containing the remains of young children in association with sacrificial rituals.

The exact nature and extent of child sacrifice in Carthage remain topics of scholarly debate, but it is generally accepted that it played a role in their religious practices during certain periods of their history. It’s important to note that this practice was not representative of all Carthaginians, and it was likely a part of their religious rituals rather than a common cultural norm.

The mention of Carthaginian child sacrifice is often brought up in historical discussions to contrast with the evolving moral values and religious practices of the Roman Empire, which expressed abhorrence toward such practices, as mentioned in the previous article. The Carthaginian practice of child sacrifice had a significant impact on the way later cultures, including the Romans, viewed and criticized it.

Evolution and context

Human sacrifice (sometimes called ritual murder), has been practiced on a number of different occasions and in many different cultures. The various rationales behind human sacrifice are the same that motivate religious sacrifice in general.

Human sacrifice is typically intended to bring good fortune and to pacify the gods, for example in the context of the dedication of a completed building like a temple or bridge. Fertility was another common theme in ancient religious sacrifices, such as sacrifices to the Aztec god of agriculture Xipe Totec.

In ancient Japan, legends talk about hitobashira (“human pillar”), in which maidens were buried alive at the base of or near some constructions to protect the buildings against disasters or enemy attacks,[6] and almost identical accounts appear in the Balkans (The Building of Skadar and Bridge of Arta).

For the re-consecration of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, the Aztecs reported that they killed about 80,400 prisoners over the course of four days. According to Ross Hassig, author of Aztec Warfare, “between 10,000 and 80,400 persons” were sacrificed in the ceremony.

Human sacrifice can also have the intention of winning the gods’ favor in warfare. In Homeric legend, Iphigeneia was to be sacrificed by her father Agamemnon to appease Artemis so she would allow the Greeks to wage the Trojan War.

In some notions of an afterlife, the deceased will benefit from victims killed at his funeral. Mongols, Scythians, early Egyptians and various Mesoamerican chiefs could take most of their household, including servants and concubines, with them to the next world. This is sometimes called a “retainer sacrifice”, as the leader’s retainers would be sacrificed along with their master, so that they could continue to serve him in the afterlife.

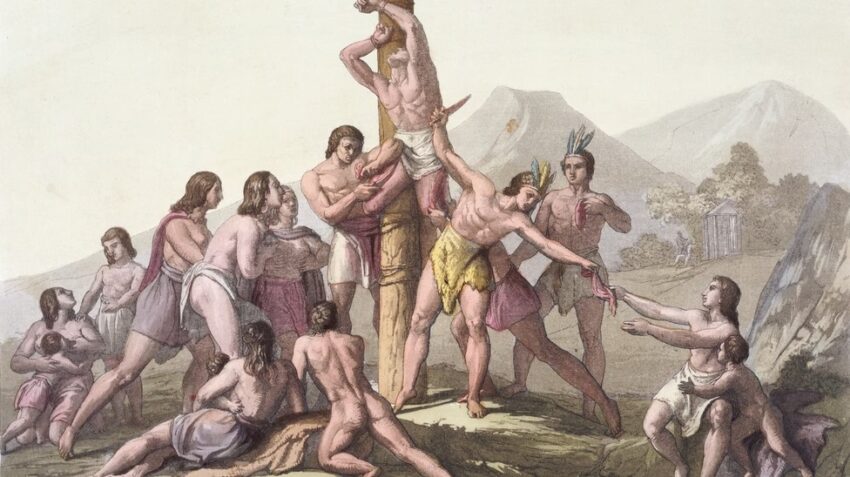

Hawaiian sacrifice, from Jacques Arago’s account of Freycinet’s travels around the world from 1817 to 1820

Another purpose is divination from the body parts of the victim. According to Strabo, Celts stabbed a victim with a sword and divined the future from his death spasms.

Headhunting is the practice of taking the head of a killed adversary, for ceremonial or magical purposes, or for reasons of prestige. It was found in many pre-modern tribal societies.

Human sacrifice may be a ritual practiced in a stable society, and may even be conducive to enhancing societal unity (see: Sociology of religion), both by creating a bond unifying the sacrificing community, and by combining human sacrifice and capital punishment, by removing individuals that have a negative effect on societal stability (criminals, religious heretics, foreign slaves or prisoners of war).

However, outside of civil religion, human sacrifice may also result in outbursts of blood frenzy and mass killings that destabilize society.

Many cultures show traces of prehistoric human sacrifice in their mythologies and religious texts, but ceased the practice before the onset of historical records. Some see the story of Abraham and Isaac (Genesis 22) as an example of an etiological myth, explaining the abolition of human sacrifice. The Vedic Purushamedha (literally “human sacrifice”) is already a purely symbolic act in its earliest attestation.

According to Pliny the Elder, human sacrifice in ancient Rome was abolished by a senatorial decree in 97 BCE, although by this time the practice had already become so rare that the decree was mostly a symbolic act. Human sacrifice once abolished is typically replaced by either animal sacrifice, or by the mock-sacrifice of effigies, such as the Argei in ancient Rome.